This week we will look a little closer into the top one percent. Who are they, what do they do, and why have their incomes increased faster than the other 99 percent?

Who are the Top One Percent?

The one-percent have been the target of campaigns against inequality over the past decade or so as a result of top incomes that are increasing faster than the national average, and no thanks to public perception of the “too big to fail” bank bailouts after the great recession and the start of the Occupy Wall Street movement. While financial sector employees do make up a substantial portion of those at the top, there are other occupation groups who may fall within the top one percent that are likely not considered when making broad-brush accusations.

According to IRS Statistics of Income, a household fell within the top one percent if their reported adjusted gross income was above $465,626 in tax year 2014. We know from the analysis of inequality trends that much of the increase in the top one percent is due to fluctuations at the very top, 0.1 percent of households, so it is also helpful to see the difference even within the top one percent. According to a report titled It’s the Market: The Broad-Based Rise in the Return to Top Talent by Steven Kaplan and Steven Rauh, in 2011 a household fell in the the top 0.1 percent with an AGI of $1.7 million. The average AGI in the top 0.1 percent was about $5 million. (Kaplan and Rauh, 37)

Race does not seem to be discussed in analyses of the top one percent, likely because it is understood even when unstated, but it is important to make clear through evidence what is presupposed by the public and by researchers alike. It is also important to recognize as a reminder of the interconnected nature of race and income in the US. A study by sociologist Lisa Kiester on The One Percent found unsurprisingly that the top 1 percent is very male, very educated, and very white compared to the bottom 90 percent. Her breakdown of demographics can be found here:

[SOURCE: Kiester, 357]

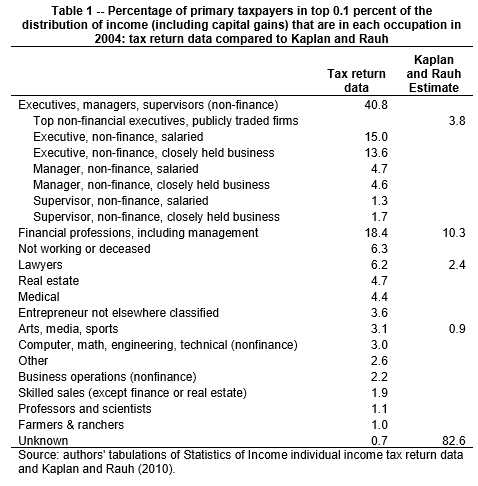

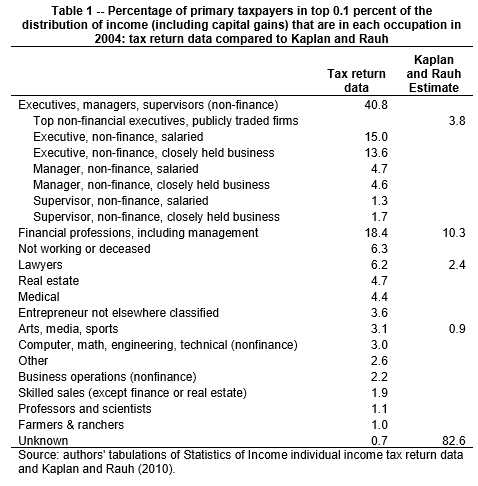

Another report by Bakija, Cole, and (IU SPEA professor) Heim, investigated the occupation makeup of the top 0.1 percent, and found that the largest group, at 40% of the top 0.1 percent are executives, managers or supervisors in non-financial sectors, while another 18.4 percent are financial professionals. However, a variety of other professions are represented in the top one percent, including doctors, lawyers, entrepreneurs, professors, and STEM occupations. They laid out the division in the following chart:

[SOURCE: Jobs and Income Growth of Top Earners and the Causes of Changing Income Inequality: Evidence from U.S. Tax Return Data,34]

Trends in the Top One Percent

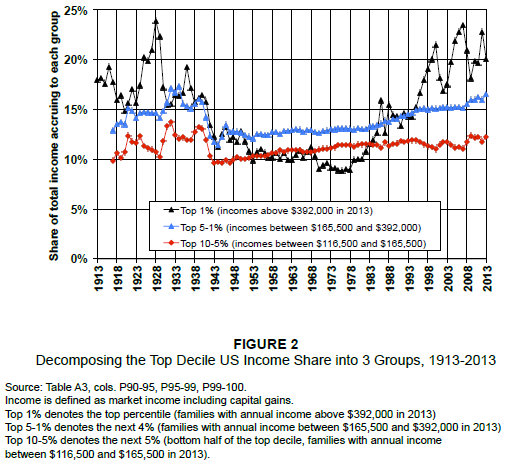

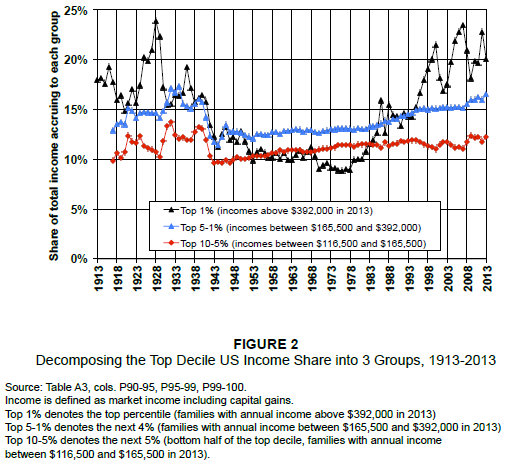

We know from the analysis of inequality trends at the beginning of this series that the one percent has increased its share of total income in the US over time, but here is a helpful reminder of that trend, with updates through 2013:

[SOURCE: Striking it Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States by Emmanuel Saez, 8]

It is clear from these trends that the top one percent has played a huge part in the increase in inequality in the United States since the 1980s, and that the longer-term trend has not changed even while the recessions have caused some volatility in top shares. Emmanuel Saez, in Striking it Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States, points out the stark inequality of growth since the great recession:

“From 2009 to 2012, average real income per family grew modestly by 6.9% (Table 1). However, the gains were very uneven. Top 1% incomes grew by 34.7% while bottom 99% incomes grew only by 0.8% from 2009 to 2012. Hence, the top 1% captured 91% of the income gains in the first three years of the recovery.” 1

Whether this trend will continue depends on a number of factors, including the causes of the increases and future policy decisions related to economic growth, regulation and redistribution.

Explanations of Gains in the Top One Percent

There are four major explanations used to explain the increasing share of income absorbed by the top one percent. These include: Globalization, Skill-Biased Technology, Superstar theory, and Compensation Norms. I will review each one briefly here.

Globalization

The globalization theory argues that the opening of borders and increasing global connectedness has increased demand for high-skilled jobs in the United States and decreased demand for low-skilled jobs, relative to demand abroad. This fits with the trend within the top one percent, in that increased labor compensation is an increasing proportion of total income. However, it does not fit a simple supply and demand framework when considering that other high income countries have not seen the same relative increases in income. For example, Saez, Piketty, Atkinson and Alvaredo in The Top One Percent in International and Historical Perspective, make the following observation:

“While other English speaking countries have also experienced sharp increases in the top 1 percent income share, many high income countries such as Japan, France, or Germany have seen much less increase in top income shares. Hence, the explanation cannot rely solely on forces common to advanced countries, such as the impact of new technologies and globalization on the supply and demand for skills.”

Skill-Biased Technology

We have reviewed this theory before, which argues that technology can act as a complement to some jobs and a substitute for others. For this theory to fit with the increase in the top one percent’s increase, it would imply that technology acts as a complement for high-skilled, high-income executive and finance jobs while acting as a substitute for lower-skilled jobs, thus increasing the compensation and share of total income going to the top one percent.

Superstars

The “superstar” explanation is a play off of the previous two theories, arguing that globalization and technology (especially communications technology) have created a situation that allows high-performing individuals to expand the scale and reach of their market base. This is most easily imagined for performing artists who are typically referred to as superstars, like singers and actors, but can also be used to explain the increases in other occupations as well. (Kaplan and Rauh, 43)

Compensation Norms

The next theory is a bit more involved, so I will spend more time on this. The compensation norms theory argues that social norms regarding increased CEO compensation have shifted to permit higher inequality within a company, and similarly argues that some of the gains at the top are due to rent-seeking behavior and information asymmetry.

Changes in pay norms:

Pay for performance and merit-based pay schemes became more common in the 80s and 90s, at the same time unionization declined. This shift away from job-based pay schedules toward merit-based fits the narrative that top compensation is partially a result of changing social norms. (Saez et. al., 11)

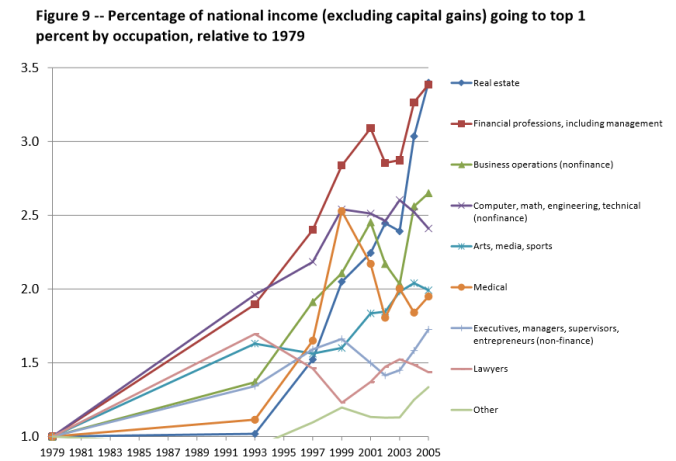

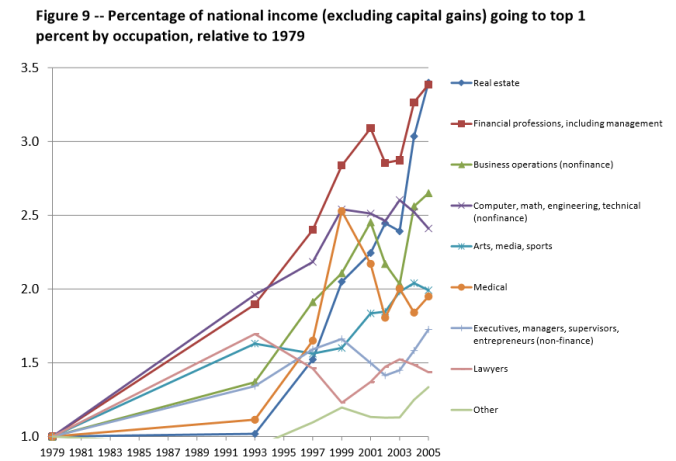

It is also evident that most of the increased share going to the top is a result of increased pay for executives and financial professionals. According to Bakija, Cole and Heim, “Executives, managers, supervisors, and financial professionals… can account for 70 percent of the increase in the share of national income going to the top 0.1 percent of the income distribution between 1979 and 2005.” (2) That divergence could be evidence that compensation norms for some occupations have changed while others have not. It may also be evidence of market inefficiency or rent-seeking behavior.

However, Kaplan and Rauh point out that the theory of changing social norms does not hold up when considering that CEOs of public corporations who are subject to peer review of compensation, have seen their pay increase by less than the pay for CEOs of private corporations whose compensation is undisclosed. By contrast we would expect the compensation to increase at similar rates if social norms related to CEO compensation were more generous. (Kaplan, Rauh, 39)

Rent-Seeking Behavior

Finally, another explanation related to compensation norms is that of rent-seeking behavior. Rent-seeking describes activities or behaviors used to increase compensation beyond a level considered market-efficient. Typically, rent-seeking behavior includes lobbying for corporate subsidies or tax incentives, but it can happen for other reasons as well, including information asymmetry or compensation spillover effects.

Bakija, Cole and Heim review the diversity of income concentration going to different occupations in the top one percent, and find considerable heterogeneity, graphed below. In particular they find that financial and real estate professionals saw the highest growth. (Page 23-4) Considering anecdotally that these increases occurred largely during the housing bubble, a period of significant deregulation of the real estate and financial sector, one could argue that this growth is not reflective of an efficient market distribution of income.

[SOURCE: Jobs and Income Growth of Top Earners and the Causes of Changing Income Inequality: Evidence from U.S. Tax Return Data by Bakija, Cole and Heim]

Other evidence of rents proposed by Josh Bivens and Lawrence Mishel, in The Pay of Corporate Executive and Financial Professionals as Evidence of Rents in Top 1 Percent Incomes, include the stark difference in CEO compensation across the globe:

“A survey by Towers Perrin, a consulting firm, shows U.S. CEO compensation was triple that of other advanced nations in 2003, up from 2.1 times foreign CEO compensation in 1988 (Mishel et al. 2004, Table 2.47). Tower Perrin also reports that U.S. CEO compensation was 44 times that of the average worker whereas the non-U.S. ratio was 19.9.” 8

Similarly, they remind readers that occupations in the financial sector (think Wall Street jobs) often have the opportunity to shift rents to themselves, particularly in situations where there is significant information asymmetry and high-risk poorly-understood financial products like CDOs on the market. (Bivens, Mishel, 9)

If they exist, these rents represent inefficiencies in the market that can be reduced without harming overall economic growth. In other words, marginal tax increases on high incomes to reduce the existence of rents would work to redistribute labor income without harming the economy. However, if the increased compensation is not a result of rents but rather market-efficient responses to increasing scale (superstar), globalization or skill-biased technologies, then tax increases may result in some adverse affect to overall economic growth.

Understanding the increase at the top of the income scale is challenging. There are a number of factors, including many unseen, making it nearly impossible to establish consensus among researchers. And of course, policy solutions will be as diverse as the explanations they accompany.

Beginning next week we will shift our focus to intergenerational mobility, looking particularly at how children of each bracket move into other (higher or lower) income brackets as adults. As always, you can contact me through my Contact Page, and find the reading list here, with updated dates: inequality-social-mobility-and-public-policy-syllabus